In this mini-project you will be writing a Python program that analyzes a DNA sequence and outputs snippets of DNA that are likely to be protein-coding genes. You will then use your program to find genes in a sequence of DNA from the bacterium Salmonella Enterica.

- Modular design

- Unit testing

- Loops

- Functions

- Conditionals

- String processing

- Data Structures

- Exceptions

- Gene detection in arbitrary DNA sequences (also known as "ab initio gene finding")

- Understanding protein coding

- Using Protein BLAST and interpreting its results

- [for the "going beyond" part] Learning how to read research papers, regulatory mechanisms for protein synthesis

Professors Ran Libeskind-Hadas created this assignment, Eliot C. Bush, and their collaborators at Harvey Mudd. Special thanks to Ran for allowing us to use this assignment and adapt it for this course.

This project is much more scaffolded by design to teach you how to write good code. Good code can mean lots of things: fast code, readable code, debuggable code, modular code, etc. One of the best ways to learn how to design and structure your own code is to see examples of well-designed software. In this project, you will have the opportunity to see a good example of modular code design. By modular we mean that the functions and their interactions have been carefully designed to create a concise, readable, and maintainable program.

Computational approaches for analyzing biological data have revolutionized many subfields of biology. This impact has been so large that a new term has been coined to describe this type of interdisciplinary fusion of biology, computation, math, and statistics: bioinformatics. The rate at which bioinformatics is growing as a field is staggering.

There are many grand challenge problems in the field of bioinformatics. In this project, we will be exploring one of these problems called "gene prediction." In the "gene prediction" problem, a computer program must take a sequence of DNA as input and output a list of the regions of the DNA that are likely to code for proteins.

Gene prediction is one of the most important and alluring problems in computational biology. Its importance comes from the inherent value of the set of protein-coding genes for other analyses. Its allure is based on the apparently simple rules that the transcriptional machinery uses: strong, easily recognizable signals within the genome such as open reading frames, consensus splice sites, and nearly universal start and stop codon sequences. These signals are highly conserved, are relatively easy to model, and have been the focus of some algorithms trying to locate all the protein-coding genes in a genome using only the sequence of one or more genomes. -- "Gene Prediction: compare and CONTRAST", Paul Flicek. Genome Biology 2007, 8:233.

One reason why this problem is so fundamental for the field is that once one knows where the protein-coding genes are, one can begin to decode the form and the function of these proteins. Once one knows the functions of these proteins, one can begin to decode the mechanisms that regulate the synthesis of these proteins (i.e. when and in what quantities these proteins are created by cells). If one can obtain a firm understanding of each of these components of the system, one gains an unprecedented level of understanding and insight into all kinds of biological processes: from understanding bacterial infection to understanding the intricacies of all sorts of cancers (and hopefully through this understanding of better treatments).

In this project, you will be writing a Python program that analyzes a DNA sequence and outputs snippets of DNA that are likely to be protein-coding genes. You will then use your program to find genes in a sequence of DNA from the bacterium Salmonella Enterica. We suspect that this particular DNA sequence is related to Salmonella's role in the pathogenesis of various diseases such as Typhoid fever. Finally, you will use the genetic search engine protein-BLAST to confirm whether or not the genes predicted by your program are in fact genes, and if so what their functional role might be. This mini-project is essentially the Biological equivalent of a mystery novel, and your primary tools, in this case, will be computational ones! More concretely, given an un-annotated text file of seemingly random symbols, you will write a Python program that will shed light on the nature of these symbols and gain insight into Typhoid fever (including aspects of how it is caused as well as the evolutionary history of the bacteria that causes the disease).

The story of Typhoid Mary is a fascinating one. It is fascinating on both scientific, legal, and philosophical levels. Rather than trying to reproduce it here, we invite you to check out the Wikipedia page on Typhoid Mary. Additionally, you may also want to listen to the fantastic RadioLab podcast called "Patient Zero". The podcast discusses a number of topics, but the first segment of the podcast is about Typhoid Mary (although, you really should listen to the whole thing; you will not be disappointed).

Image source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Typhoid_Mary

In this mini-project, we will be building a gene finding program that can accurately determine regions of the Salmonella bacterium's DNA that code for proteins.

The first step to getting started on this mini-project is to get a copy of the starter files on your computer.

Clone the repository to your computer by typing the following into your terminal program. Replace myname with your GitHub user id.

(note: these commands will clone your GeneFinder repository in your home directory, please modify the first line to cd to a different directory if you'd rather clone somewhere else).

$ cd ~

$ git clone https://github.com/PythonMiniProject2020-myname.git GeneFinder

$ cd GeneFinder

$ ls *The last command will show you all of the files in the GeneFinder repository. The next section explains the purpose of each of these files.

The last step of the previous section had you listing the contents of the

GeneFinder. Here is a description of each of the files:

gene_finder.py: this is where you will put your code for this mini-project.amino_acids.py: some predefined variables that will help you write code to translate from DNA sequences to amino acid sequences.load.py: some utility functions for parsing and then loading the files in the data directory.data/X73525.fa: a FASTA file containing part of the genetic code of the Salmonella bacterium. This part of the genetic code is responsible for some aspects of Salmonella pathogenesis.data/3300000497...,data/nitrogenase... :genetic for the metagenome Going Beyond extension.

The first thing to do is to use a text editor to open up'gene_finder.py`.

This file has been populated with function declarations, docstrings, and unit tests for all the functions you will need to complete the project. Start reading through the functions declared in the file. The (the Wikipedia article for Open-reading Frame is a good place to start) to refresh on the requisite concepts.

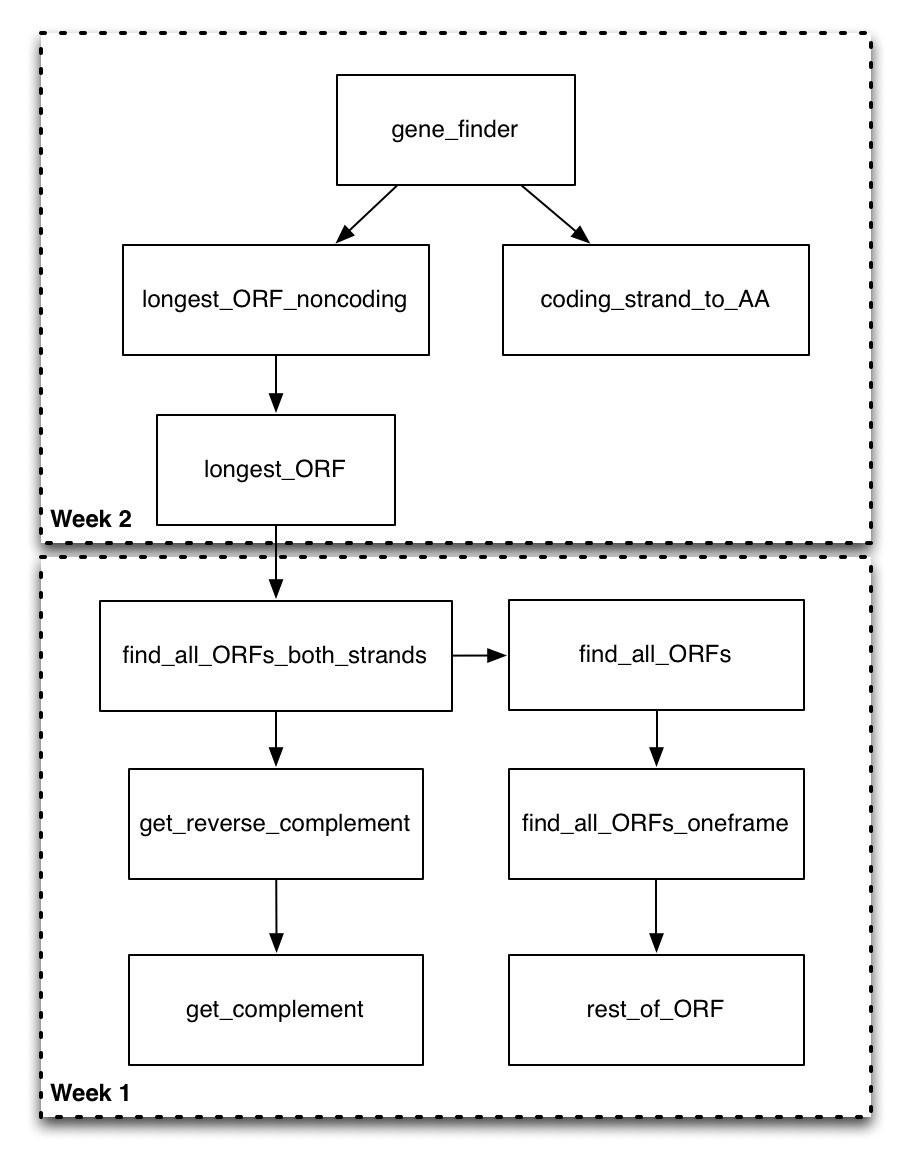

Now that you have a good sense of the functions you will be filling out, take a look at this function diagram.

This diagram shows all of the program's functions and uses a directed arrow to indicate that the function on the "from" side of the arrow calls the function on the to side of the arrow. At this point, some of these arrows might make complete sense (you know exactly why and how the functions would interact). Others will be less obvious. That's okay! You don't have to necessarily understand every aspect of the design before you start on the mini-project. The idea is that the motivation for the design will become apparent as you implement parts of it.

We could start by trying to implement any particular box in this diagram. However, we are going to be doing our implementation in a bottom-up ordering. That is, we are going to be implementing the functions that are called by other functions before we implement the calling functions. The motivation for this is that once you have had the experience of implementing the called function (on the "to" side of the arrow), it should be more clear how it can be utilized in the calling function (on the "from" side of the arrow).

For the first part of the project, you will be creating some utility functions that will help you build your gene finder. Open up gene_finder.py and fill in your own implementations of the functions described below.

For each function, we have given you some unit tests (using doctest). You will want to add additional unit tests (again using doctest). For each unit test you add, write a sentence(ish) explaining your rationale for including the unit test. If you think the unit tests we have given you are sufficient, please explain why this is the case. This additional text should be included in the docstring of the function immediately before the relevant unit test.

Also, if you want to test a specific function (in this example, we will test get_complement) rather than running all of the unit tests you can modify the line at the end of the program from:

"`python doctest.testmod()

to:

```python

doctest.run_docstring_examples(get_complement, globals())

If you want to see verbose output of your doctests, set the verbose flag to True:

"`python doctest.run_docstring_examples(get_complement, globals(), verbose=True)

For this part of the project, you will write code that takes a DNA sequence and returns a list of all open reading frames in that sequence. Recall that an open reading frame is a sequence of DNA that starts with the start codon (ATG) and extends up to (but not including) the first in frame stop codon (TAG, TAA, or TGA). Open up `gene_finder.py` and fill in your own implementation of the functions described below:

* `get_complement`: this function should take a nucleotide as input and return the complementary nucleotide.

To help you get started here are some unit tests (make sure you have read the

[Unit Testing Instructions](#unit-testing-instruction)):

```python

>>> get_complement("A")

'T'

>>> get_complement("C")

'G'

get_reverse_complement: this function should return the reverse complementary DNA sequence for the input DNA sequence.

To help you get started here are some unit tests (make sure you have read the Unit Testing Instructions):

>>> get_reverse_complement("ATGCCCGCTTT")

'AAAGCGGGCAT'

>>> get_reverse_complement("CCGCGTTCA")

'TGAACGCGG'rest_of_ORF: Takes an input sequence of DNA that is assumed to begin with a start codon, and returns the snippet of DNA from the beginning of the string up to, but not including, the first in frame stop codon. If there is no in frame stop codon, the whole string is returned.

Some unit tests (make sure you have read the Unit Testing Instructions):

>>> rest_of_ORF("ATGTGAA")

'ATG'

>>> rest_of_ORF("ATGAGATAGG")

'ATGAGA'find_all_ORFs_oneframe: this function should find all open reading frames in a given sequence of DNA and return them as a list of strings. You should only check for ORFs that start on multiples of 3 from the start of the string. Your function should not return ORFs that are nested within another ORF. To accomplish this, once you find an ORF and add it to your list, you should skip ahead in the DNA sequence to the end of that ORF. You will find awhileloop to be useful for this purpose. Make sure to utilize yourrest_of_ORFfunction when coding this part.

A unit test (make sure you have read the Unit Testing Instructions):

>>> find_all_ORFs_oneframe("ATGCATGAATGTAGATAGATGTGCCC")

['ATGCATGAATGTAGA', 'ATGTGCCC']find_all_ORFs: this function should find all open reading frames in any of the 3 possible frames in a given sequence of DNA and return them as a list of strings. Note that this means that you need to check for ORFs in all three possible frames (i.e. with 0, 1, and 2 offset from the beginning of the sequence). For example, you would want to consider the following codon groupings when looking for all ORFs (groups of +++ or --- indicate that the nucleotides above are considered as a single codon).

ATGTGAAGATTA

+++---+++---

-+++---+++--

--+++---+++-

As in above, don't include ORFs that are nested within other ORFs. Your

function should heavily utilize find_all_ORFs_oneframe.

A unit test (make sure you have read the Unit Testing Instructions):

>>> find_all_ORFs("ATGCATGAATGTAG")

['ATGCATGAATGTAG', 'ATGAATGTAG', 'ATG']find_all_ORFs_both_strands: this should do exactly the same thing asfind_all_ORFs,except it should find ORFs on both the original DNA sequence and its reverse complement.

A unit test (have you read the Unit Testing Instructions?) ;-)

>>> find_all_ORFs_both_strands("ATGCGAATGTAGCATCAAA")

['ATGCGAATG', 'ATGCTACATTCGCAT']List comprehensions! Many of these functions can be written more succinctly using list comprehensions (see Section 5.1.3 here). Try to use list comprehensions to rewrite some of your code. Were any of the functions particularly hard (or impossible) to rewrite using list comprehensions? If so, how come?

In this section, you will be implementing the rest of the functions necessary to create your gene finder. Once you have done that, you will be using your code to analyze a real DNA sequence suspected to play a role in Typhoid fever.

longest_ORF: Finds the longest open reading frame on either strand of the DNA. Make sure you leverage code from previous parts of the mini-project.

A unit test (make sure you have read the Unit Testing Instructions):

>>> longest_ORF("ATGCGAATGTAGCATCAAA")

'ATGCTACATTCGCAT'longest_ORF_noncoding: this function takes as input a DNA sequence and an integer indicating how many random trials should be performed. For each random trial, the DNA sequence should be shuffled and the longest ORF should be computed. The output of the function should be the length of the longest ORF that was found across all random trials (that is the output oflongest_ORF_noncodingis an integer). In order to test this code you may find it useful to use the provided Salmonella DNA sequence. For example, if you find the longest ORF of 700, 600, and 300 on your three random trials, this function should output 700.

Note 1: To randomly shuffle a string, you should use the provided shuffle_string function.

If you wanted to implement this function yourself, you could take the following approach:

- First, convert the string to a list using the

listfunction. - Once you have a list, you can shuffle the list using the built-in python function

random.shuffle. - To reassemble the shuffled list back to a string, you can use the string

joinfunction.

Note 2: We are not going to create unit tests for this function. Why not? Can you think of a different method of unit testing that would be appropriate for this function? Are there any other methods you might use to build confidence that your implementation is correct?

coding_strand_to_AA: this function converts from a string containing a DNA sequence to a sequence of amino acids. The function should read triplets of DNA nucleotides (codons), look up the appropriate amino acid (either using the provided variables inamino_acids.pyor by encoding this information yourself), concatenate the amino acids into a string, and then return the amino acid sequence from the function.

You can convert a three nucleotide string (also called a triplet codon) into the appropriate amino acid in the following manner.

amino_acid = aa_table['CGA']amino_acid will now be the string 'R' (which stands for Arginine).

If you wanted to implement your own lookup, you could use the lists aa and codons to complete the mapping. codons is a list of lists where codons[i] contains a list of codons that code for the amino acid stored inaa[i].

Some unit tests (make sure you have read the Unit Testing Instructions):

>>> coding_strand_to_AA("ATGCGA")

'MR'

>>> coding_strand_to_AA("ATGCCCGCTTT")

'MPAgene_finder: this function takes as input a sequence of DNA. First, use yourlongest_ORF_noncodingon the input DNA sequence to compute a conservative threshold for distinguishing between genes and non-genes by runninglongest_ORF_noncodingfor 1500 trials. For instance, the first line of yourgene_finderfunction might be:

"`python threshold = longest_ORF_noncoding(dna, 1500)

Next, find all open reading frames on both strands, and then return a list

containing the amino acid sequence encoded by any open reading frames that are longer than the threshold computed above using `longest_ORF_noncoding`.

To tie it all together, you will actually be applying the `gene_finder` program that you wrote to some real DNA! It is this type of computational sleuthing that has helped unlock many secrets. The first step is to get some DNA to analyze. The `data` folder has a FASTA file containing a sequence of DNA from Salmonella Enterica believed to be related to its pathogenesis. To load the sequence as a FASTA file, use the provided `load_seq` function.

```python

>>> from load import load_seq

>>> dna = load_seq("./data/X73525.fa")

Use your gene_finder function on the Salmonella DNA sequence to get a list

of candidate genes.

Also, if you are interested in comparing the results of your gene finder to a state-of-the-art one, you can try out one called Glimmer here.

To turn in your mini-project, make sure that your work is pushed to your GitHub repository.

For the main project, all your code will be in gene_finder.py. If you

choose to do the Going Beyond portion, it is up to you how you structure your code for that portion.

For this section, you will be analyzing a meta-genome. In metagenomics, communities of microbes are analyzed using samples directly collected from the environment (instead of using lab cultures). The benefit of this approach is that it gives better insight into the diversity of microbes in the wild and how this diversity contributes to the functioning of the community. The downside is that it is more difficult computationally to analyze the genetic material collected from these communities. In this portion, you will be writing a program to determine which microbe represented in a mystery meta-genome is responsible for Nitrogen fixation.

The first step is to load the data. There are two functions in the load.py

file that will help you get started. The first loads a sequence of DNA that is known to code for Nitrogenase (an enzyme crucial in the Nitrogen fixation

process).

>>> from load import load_nitrogenase_seq

>>> nitrogenase = load_nitrogenase_seq()

>>> print(nitrogenase)

'ATGGGAAAACTCCGGCAGATCGCTTTCTACGGCAAGGGCGGGATCGGCAAGTCGACGACCTCGCAGAACACCCTCGCGGCACTGGTCGAGATGGGTCAGAAGATCCTCATCGTCGGCTGCGATCCCAAGGCCGACTCGACCCGCCTGATCCTGAACACCAAGCTGCAGGACACCGTGCTTCACCTCGCCGCCGAAGCGGGCTCCGTCGAGGATCTCGAACTCGAGGATGTGGTCAAGATCGGCTACAAGGGCATCAAATGCACCGAAGCCGGCGGGCCGGAGCCGGGCGTGGGCTGCGCGGGCCGCGGCGTCATCACCGCCATCAACTTCCTGGAAGAGAACGGCGCCTATGACGACGTCGACTACGTCTCCTACGACGTGCTGGGCGACGTGGTCTGCGGCGGCTTCGCCATGCCGATCCGCGAGAACAAGGCGCAGGAAATCTACATCGTCATGTCGGGCGAGATGATGGCGCTCTATGCGGCCAACAACATCGCCAAGGGCATCCTGAAATACGCGAACTCGGGCGGCGTGCGCCTCGGCGGCCTGATCTGCAACGAGCGCAAGACCGACCGCGAGCTGGAACTGGCCGAGGCCCTCGCCGCGCGTCTGGGCTGCAAGATGATCCACTTCGTTCCGCGCGACAATATCGTGCAGCACGCCGAGCTCCGCCGCGAGACGGTCATCCAGTATGCGCCCGAGAGCAAGCAGGCGCAGGAATATCGCGAACTGGCCCGCAAGATCCACGAGAACTCGGGCAAGGGCGTGATCCCGACCCCGATCACCATGGAAGAGCTGGAAGAGATGCTGATGGATTTCGGCATCATGCAGTCCGAGGAAGACCGGCTCGCCGCCATCGCCGCCGCCGAGGCCTGA'The second step is to load the meta-genome. Again, there is a function in the

load.py file loads the meta-genome for you. Be sure to understand how it works.

>>> from load import load_metagenome

>>> metagenome = load_metagenome()

>>> print(metagenome[0])

('Incfw_1000001',

'AACAGCGGGGAATCGTCGACGCAATGCGCGGCATACAGCGTGCCGGCGAGCCCGGCCGACAGAAGACCGGCGAGCGCCCCGGCGAGCGCCGGGCGCGACGGCGCGCCGCGGCGCAGGCCCATCAGCGCGGCACCGAGGAACGGTAGCGACAGCACCGGGATCGAGCCGAGACACAGCAGCGAGTTGTGACCGAGCAGCCGCGTCATCGCCGAGGTTCGATGCGGCAGCATCGCTTCGGCGCCGATCGCGAGGCCGAGGATCGCCAGCGGCGCCAGCAGCAGCAGGCGCCAGCCTTTCGCCGTCGCCTCCGGGCGCGACAGATGCAGCGCGACGATGATCGC')The variable metagenome contains a list of tuples. Each tuple consists of the name of a DNA snippet and a DNA sequence.

Next, write a program to determine which of these DNA snippets (in metagenome) are responsible for Nitrogen fixation. If all Nitrogenase genes looked the same, this would be relatively straightforward. You would simply loop through all the snippets until one matched the Nitrogenase sequence exactly. However, there are a variety of different Nitrogenase genes. Fortunately, there are fairly large portions of the given Nitrogenase sequence that are conserved (meaning they are the same in almost all genes that code for Nitrogenase). The approach we are going to use to determine whether or not a given snippet is likely to code for a form of Nitrogenase is called longest common substring. The idea is that if we relax our criteria for matching the Nitrogenase sequence exactly, we will still be likely to find the conserved portion of the sequence in our metagenome.

Your program should loop through all of the snippets in the metagenome and compute the longest common substring between the snippet and the Nitrogenase sequence. The snippets that have the longest common substrings with the Nitrogenase reference sequence are likely to code for Nitrogenase. Which are these? What are the longest common substrings?

There are several ways to solve the longest common substring problem. The most straightforward is to use a nested for loop over all possible start positions in both the Nitrogenase and the DNA snippet. For each possible combination of start positions, you then loop through both strings until you find corresponding characters that don't match. Keep track of the longest substring found so far, and after you have checked all possibilities, return this longest match.

1. Use PyPy to execute your program (a modified Python interpreter that excels when executing Python programs that depend heavily on loops). I got a 30 fold speedup when using the simple approach to longest common substring described above.

Linux: To install this run sudo apt-get install pypy.

macOS: Install home brew, and then run brew install pypy.

2. Implement a smarter algorithm for longest common substring (the dynamic programming solution is the next logical one to try).

3. Use the Python multiprocessing library to use all the processor cores on your laptop to examine several snippets at once. Also see An introduction to parallel programming using Python's multiprocessing module.

Read more about other approaches to gene-finding in prokaryotes. If you are really gung-ho, pick one, and implement it!

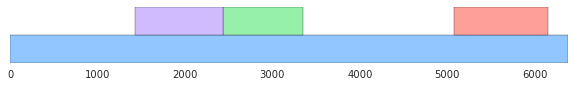

- Visualize the data:

For example, generate a picture that shows where the genes are in the DNA strand. Some libraries to look into are:

- Matplotlib. [The image below uses Matplotlib, with a color palette from Seaborn.] Matploglib is a good library to learn if you want to use Python for statistical data visualization; add Seaborn if the default Matplotlib settings offend your visual aesthetics.

- Kivy for interactive user interfaces.

You can also explore:

- Draw a histogram that compares the lengths of the genes found to the lengths of the noncoding ORFs from the shuffled sequences.

- Graph the similarity of different snippets to the nitrogenase sequence in Going Beyond

- Draw the sequence above as a circle, rather than a line.